One of the most difficult aspects of co-authoring a memoir or other non-fiction book is taking good notes. When you’ve just started working with a new client, among all the tasks you have to complete, properly interviewing that client and taking notes is a step that can’t be overlooked.

But interviewing the client is not as easy and straightforward as it seems. This is not like sitting in class. There’s more to it. Here are a few pointers to help you on your way.

1. Ask Questions – But Only When You Have To

This may seem like an odd pointer for taking notes, especially when you’re relatively unfamiliar with the person you’re interviewing, but the process is really an art not a science. In other words, if you go into an interview with a forensic kind of outlook then you’re not going to get the most from your client. You’re client is a human not a lab rat.

Pressing a person to answer your prearranged questions is a great way to get them to clam up, which is the last response you want to elicit. Above all else, you must make them comfortable and get them talking.

2. Do Your Best to Get Them Talking

It doesn’t matter what you think or what stories you have to tell, you’re not writing your own book. Assuming you’re ghostwriting a memoir or another non-fiction book where you, the author, are not the subject, your job then is to listen and take notes and ask questions only when you need clarification or to keep the ball rolling.

I have been accused from time to time of not asking enough questions. But that usually comes when the person I’m interviewing has finished telling a story. That’s the moment when you prompt them to help keep up the momentum, and keeping up their momentum is your number one task.

3. Get Them to Tell Their Story

In my experience if someone has an interesting tale stored inside them, even if they’re not the biggest talker, you can get them to chat and to open up about their special subject without too much effort – mostly just get out of the way.

You can guide the conversation as it goes along, but from my point of view the main job of a ghostwriter or co-author who’s interviewing a client is to get them to tell their story in as much detail as they can stand to tell it in.

4. Neither Too Much Nor Too Little

You can’t seem like a prosecuting attorney. However, you can’t seem like a pupil in a classroom either. You are there to soak up what the client has to say, but since they are not a professional speaker (unless of course they are) then you’re going to have to engage them in a conversation of which they are the subject.

5. Notes

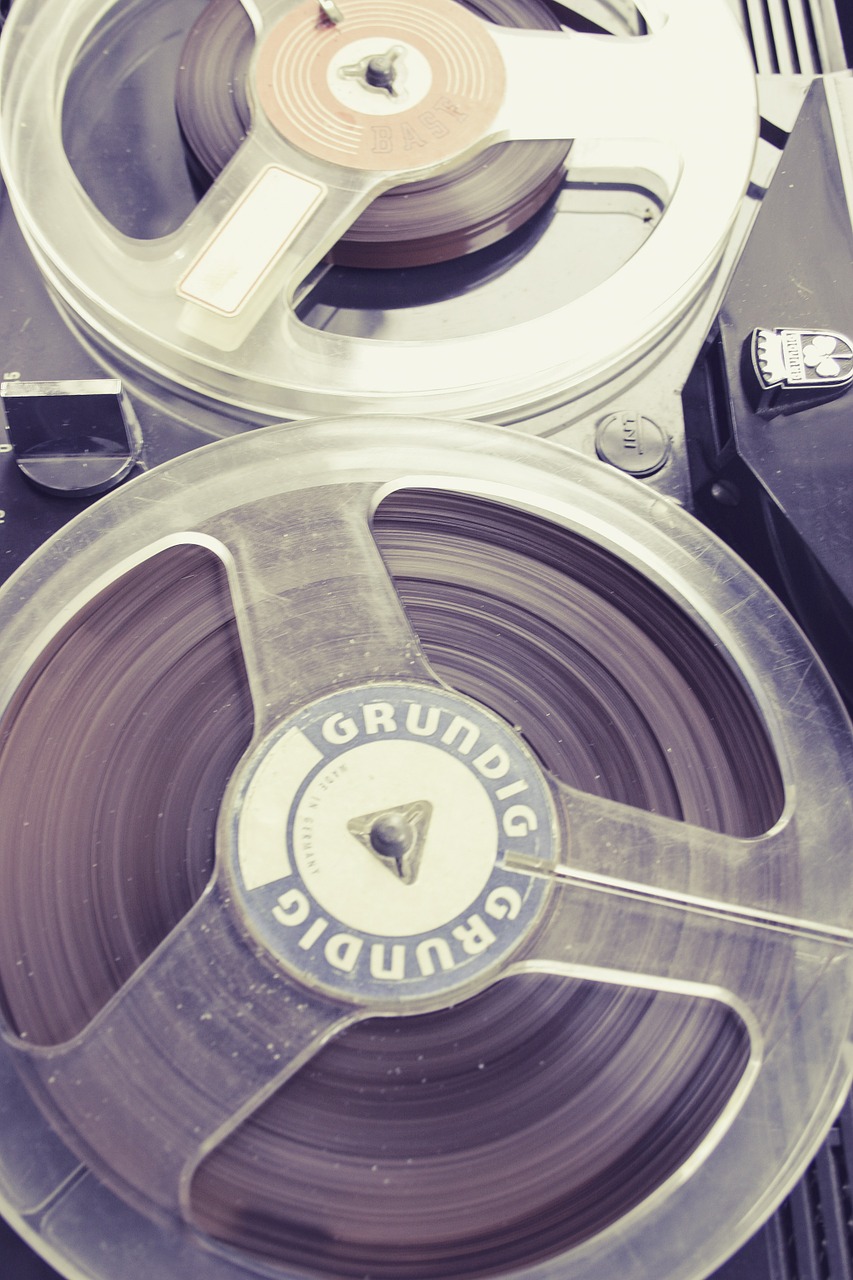

As for note taking, write down every word your client says and bring a tape recorder. Periodically jot the time sequence down in your notes so you can jump into the recording at that point, especially when the details are relevant.

Closing

You’re job is to coax your client along, ask leading questions, clarify, and most of all encourage them to tell their story. I visualize my interviews as conversations with a point. My goal is to get their story, in their words. Your client is the star. They have a unique perspective, which it’s your job to capture.